Chestny ZNAK

The new Russian track & trace system (Chestny ZNAK) launched in March 2019 is probably the most comprehensive system of control of the movement of goods established by any tax authority in the world.

It all started with some stamps on liquor (EGAIS). Subsequently, there was the introduction of Cash Register Equipment (CRE) and the pilot making RFID chip tagging of fur items mandatory.

Chestny ZNAK is already mandatory for tobacco, fur, footwear and some medications. Pilots for dairy, wheelchairs, bicycles, photo cameras, tyres, garment and perfumes are carried out or starting next month. According to the tax authorities, by 2024, the system will cover all consumer industries.

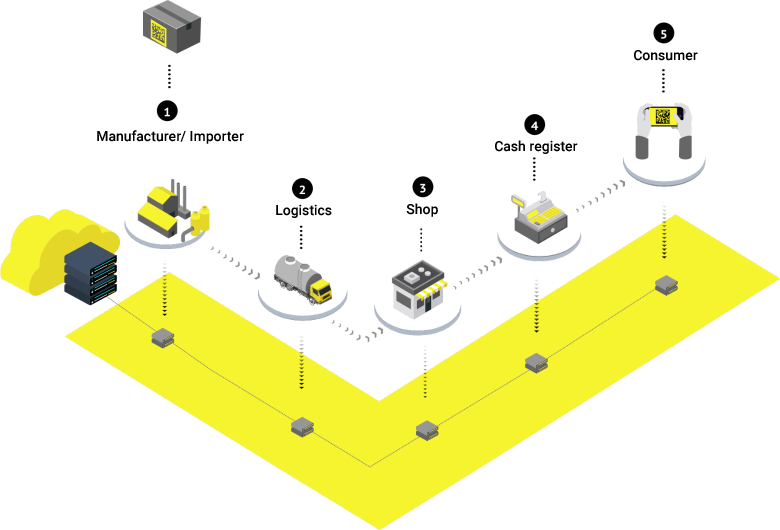

How does it work?

To each product manufactured or imported to Russia, there has to be assigned a unique digital code and placed on the packaging. With the help of this code Chestny ZNAK records the transfer of goods, when goods are stored or placed on the shelf and when items are sold via an online cash register. There is even an end consumer app that allows scanning the purchased product.

In this way, Chestny ZNAK makes it possible to trace the entire journey of the product.

Poland and Italy are also planning to introduce online cash registers.

Is this the direction we all are heading?

The 2019 Bulgarian tax authority hack has taught us two things:

First, tax authorities are probably already collecting a lot more data than they tell us and than we think.

After the hack in Bulgaria 57 databases with 10.7 GB of data were shared in a forum. The hacker claimer that 110 databases with nearly 21 GB were stolen. The data contains names, personal identification numbers, home addresses, financial earnings, debt information, health and pension payments and so on of 5 million Bulgarians (out of 7 million, i.e. just about every working adult) ranging from 2007 to June 2019. The data also contains information imported to the tax authority’s systems from many other government agencies such as customs agency (BECIS system), Department Civil Registration and Administrative Services (GRAO), National Health Insurance Fund (NZOK) and Bulgarian Employment agency (AZ).

But most interestingly, officials said that this is only 3% of the data they have!

Second, the authorities don’t seem to have understood the real value / damage potential of this data yet and fail to secure it accordingly.

The hacker seemed to use SQL injection to gain access to the databases through a rarely used VAT refund service for transactions abroad. This VAT refund service was implemented in 2012, but not updated since. Since SQL injection is no rocket science, this leaves the impression of poorly secured and protected data.

Since 2002, the Bulgarian government has spent estimated more than $1 billion (about 2 billion BGN) on e-government projects. At the same time, a 2018 annual report on the state of national security already indicated a very low level of cybersecurity insufficient to counter modern challenges, but obviously no adequate action was taken.

What happens when the taxman gets superpowers?

On June 25th, we launched our new book at this year’s EMEA Global Relationship Partner (GRP) Conference held in Lisbon.

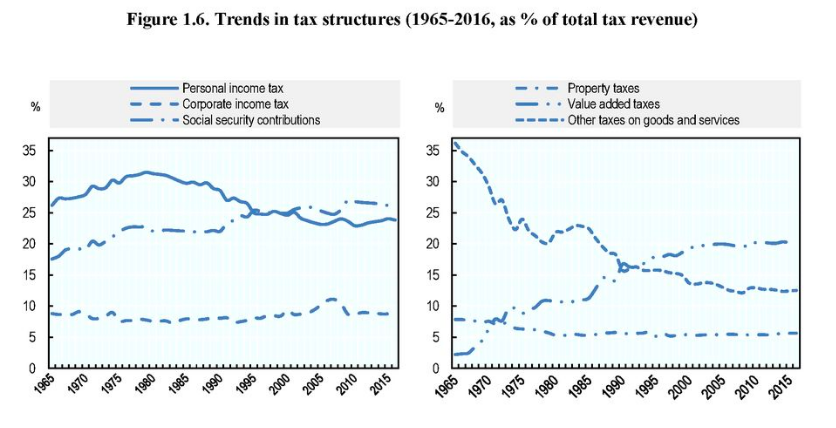

The rise of VAT and the impact of digitalisation

The rise of value-added tax (VAT) in the last decades is stunning.

Source: OECD (2018), Revenue Statistics 1965 – 2017, p. 29

I ask myself what the long-term impact of digitalisation will be. My guess would be that it becomes even more important and its share of total tax revenue further increases. On the one hand, VAT can easily be extended to the sale of digital products and services. On the other hand, I observe that tax administrations unroll digital technology first and massively in the area of VAT (it’s less complicated than corporate tax, for example). This makes control cheap and efficient, especially in the area of digital services, and will help a lot improving taxpayer compliance and increasing revenue.

GDPR Vs. Digital Service Tax / Block chain

Maybe I am wrong, but I have the impression that the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is contradicting both the principles of the European proposal for Digital Service Tax (DST) and the principles of the strongly pushed blockchain technology. The GDPR requires you, for example, to delete a lot of (personal) data you collect. The DST in contrast requires you to collect a lot of data (e.g. geo-localisation of users) for accounting, record-keeping and other obligations intended to ensure that the DST is effectively paid. The GDPR tries to grant privacy and the right to erasure. The blockchain tries to grant that records are transparent and cannot be changed.

Every function does it’s own thing, that is common. But from time to time some coordination and a consistent overall digital strategy could be useful.

Machine Learning takes it to the next level

Enzymes and the Big 4

The Aadhaar Example

Societal benefits of the widespread use of digital technologies by the public administrations will be huge. Equally huge will be the potential of misuse. This potential will unfold incrementally and therefore hardly noticed or almost irreversible. But rejecting the use of digital technologies is no (smart) option. Rather (digital) institutional design is key.

India‘ Aadhaar ID system may serve as a good example what I mean by unfolding incrementally and irreversibly. In 2009 established on voluntary basis to help the poor get welfare benefits, it quickly became the world’s largest biometric ID system. Modi made it de facto mandatory to fight corruption and inefficiency. 99% of India’s 1.3 billion total population are now enrolled in Aadhaar. As a result the Aadhaar ID is de facto needed for a mobile contract, credit card, insurance, social allowance, or even for train tickets… And of course, every transaction linked to Aadhaar is tracked by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIAI).

For a full story on Aadhaar see https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/07/technology/india-id-aadhaar.html

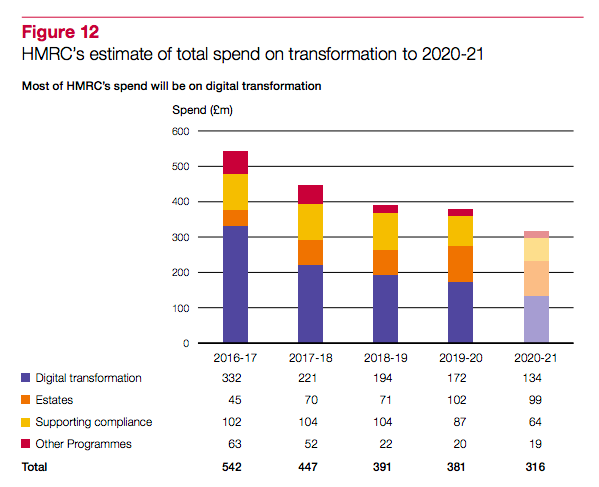

HMRC’s estimate of total spend on digital transformation

The HRMC may serve as a good example for the digital transformation efforts public administrations are quietly but resolutely making. Their current investment plan includes expenditures on digital transformation in the amount of GBP 332m in 2016/17, GBP 221m in 2017/18, GBP 194m in 2018/19, GBP 172m in 2019/20 and GBP 134m in 2020/21. This adds up to an investment of more than GBP 1 billion over the next five years – just in digital technologies. Not even included are the accompanying investment costs for estates, supporting compliance and so on. The overall costs of the transformation process add up to more than GBP 2 billion in five years.