Chestny ZNAK

The new Russian track & trace system (Chestny ZNAK) launched in March 2019 is probably the most comprehensive system of control of the movement of goods established by any tax authority in the world.

It all started with some stamps on liquor (EGAIS). Subsequently, there was the introduction of Cash Register Equipment (CRE) and the pilot making RFID chip tagging of fur items mandatory.

Chestny ZNAK is already mandatory for tobacco, fur, footwear and some medications. Pilots for dairy, wheelchairs, bicycles, photo cameras, tyres, garment and perfumes are carried out or starting next month. According to the tax authorities, by 2024, the system will cover all consumer industries.

How does it work?

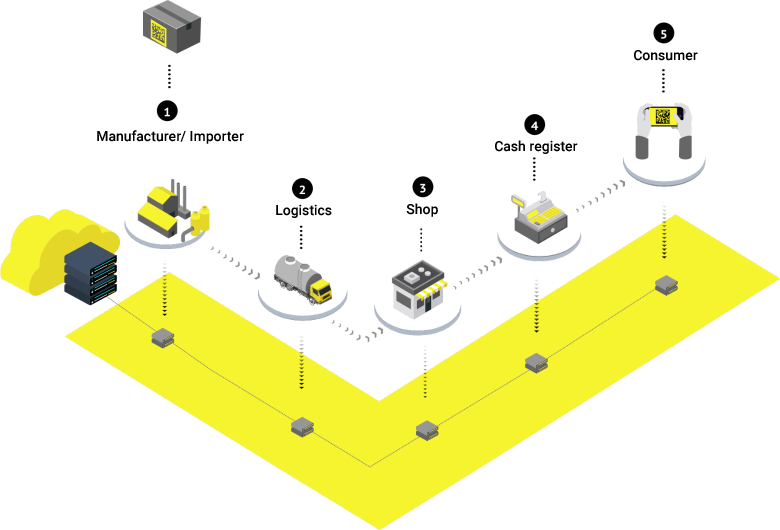

To each product manufactured or imported to Russia, there has to be assigned a unique digital code and placed on the packaging. With the help of this code Chestny ZNAK records the transfer of goods, when goods are stored or placed on the shelf and when items are sold via an online cash register. There is even an end consumer app that allows scanning the purchased product.

In this way, Chestny ZNAK makes it possible to trace the entire journey of the product.

Poland and Italy are also planning to introduce online cash registers.

Is this the direction we all are heading?

The 2019 Bulgarian tax authority hack has taught us two things:

First, tax authorities are probably already collecting a lot more data than they tell us and than we think.

After the hack in Bulgaria 57 databases with 10.7 GB of data were shared in a forum. The hacker claimer that 110 databases with nearly 21 GB were stolen. The data contains names, personal identification numbers, home addresses, financial earnings, debt information, health and pension payments and so on of 5 million Bulgarians (out of 7 million, i.e. just about every working adult) ranging from 2007 to June 2019. The data also contains information imported to the tax authority’s systems from many other government agencies such as customs agency (BECIS system), Department Civil Registration and Administrative Services (GRAO), National Health Insurance Fund (NZOK) and Bulgarian Employment agency (AZ).

But most interestingly, officials said that this is only 3% of the data they have!

Second, the authorities don’t seem to have understood the real value / damage potential of this data yet and fail to secure it accordingly.

The hacker seemed to use SQL injection to gain access to the databases through a rarely used VAT refund service for transactions abroad. This VAT refund service was implemented in 2012, but not updated since. Since SQL injection is no rocket science, this leaves the impression of poorly secured and protected data.

Since 2002, the Bulgarian government has spent estimated more than $1 billion (about 2 billion BGN) on e-government projects. At the same time, a 2018 annual report on the state of national security already indicated a very low level of cybersecurity insufficient to counter modern challenges, but obviously no adequate action was taken.